Alrighty Then – Part 1

I like to be right. In fact it would be fair to say, I’m obsessed with being right. I certainly don’t like to be wrong, and just quietly, I have worked hard to make sure I don’t find myself in that place where I might appear to be without all the answers. And that is all well and good until some bright spark pops up with a truly deep and disturbing question, the answer to which I have not a clue.

Are you like that?

When I do come to the awareness that I might be wrong, apart from feeling vastly uncomfortable, I like to be the one who comes up with the apology, as if it was my idea in the first place. I really dislike finding myself in a place where someone is taking the opportunity to let me know I am wrong, how I am wrong, and what I should do to fix it. This is not a happy place for me, and I avoid it.

Are you like this?

This sort of behaviour might sound problematic, and I would be the first to examine it, and come up with justifications—after all, I just want to do what is right.

It is at this point I realise I really need to look at my motivation.

Do I do what is right because I love God? Is it because I love other people, and want the best for them? Or is it more a case of I don’t want to look bad? Well, to be perfectly honest, I don’t want to look bad. Does anybody like looking bad? This often leads me to the place where I become addicted to being right all the time. But there is a major flaw in this plan.

The older I get, the more I realise there are things I do not know. What person on this earth can possibly be right all the time? How can any one of us know all there is to know about everything—from the outer reaches of the universe to the inner worlds of macro biology, no one can know it all. And that doesn’t even take into account all the philosophical, emotional and spiritual questions that could be asked.

So these questions exist and they beg to be answered: What is right? What is truth?

I do know this, despite my addiction to wanting to appear to be right, I do not have a corner on truth and righteousness. Just because I want to do what is right does not always make me right.

When I began to think about this conundrum, I was well aware of a number of contentious issues that were being highlighted in media and social media arguments. I wanted to know the RIGHT answers, and wished I could contribute from a place of some authority. But I am not an authority on everything that needs to be examined—theology, psychology, philosophy, scientific research etc. I know stuff, but not everything there is to know. Still I was troubled by what was being presented. I took out my notebook and began a list of contentious issues that are bound to raise hackles, if not passions. By the time I had finished the list, there were twenty-two issues written down. Over half of them were social issues represented by social justice groups. Now despite the fact that you might wish me to publish this list of contentious issues, I do not intend to, and this is the reason why:

Religious groups often feel they must take a ‘position’ on these issues, and that these positions must be made clear. This often throws fuel on the fire, and manages to end up burning not only the members of the religious groups, but also the folks affected by the issues.

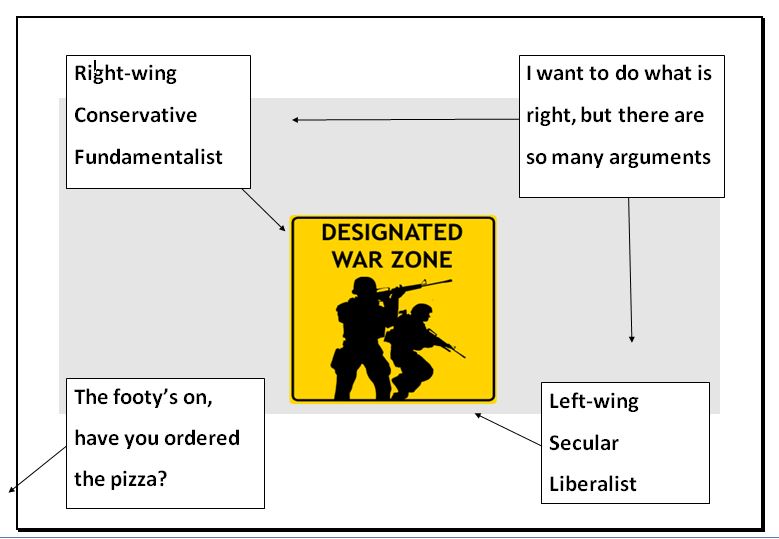

Let me draw a picture so we can have a look at what is happening in our current western society.

Imagine a whole group of people in a large open space room, and that you are amongst the crowd. The four corners of the room are designated corners to represent your opinion or position on any given issue. For the sake of the exercise, I am going to label the corners as follows:

- Right winged, conservative, fundamentalist

- Left winged, secular, liberalist

- ‘I want to do what is right, but with so many arguments I’m not sure’ (uncertain)

- The footy is on. Have you ordered the pizza? (indifferent)

I call out an issue, and you go to the corner that best represents your thoughts and stand on that issue.

From my observation of social media and some news reports, most of the issues I have written down on my list are not only contentious, they are polarised. That is to say, extreme groups quickly form in opposite corners and are often angry, aggressive and sometimes violent. Including right-winged conservative Christians, who can sometimes use violent words. Folks in the uncertain group seem to stand on the edges, anxiously wringing their hands, wanting to make things right, not knowing how, thinking at best, they might avoid a fight. Folks in the indifferent corner get busy with whatever they have at hand to distract them.

That place in the middle is a war zone. This is a place where folks should be able to come to discuss and reason, but alas, you enter at your own risk. Some of the responses to blog posts and media reports that I have read have been ugly and vicious, and certainly make me think twice before opening my big mouth and offering an opinion. I have observed that when an action or comment has been judged as offensive or insensitive by one group, the other group rises up in anger—lighted torches and pitch forks in hand to kill the beast. The various news media groups replay certain words, pictures and footage over and over again, not to soothe the savage beast, but to infuriate and stir the issue. It sells papers and gets ratings—and it fairly burns in cyber world as the passions of social media users boil over and spew acid and venom.

Here is another little secret, I not only like to be right, I like being liked. I have opinions and ideas about various matters, but that place in the middle is not a stable or safe place to talk. People lose perspective quickly, and words are often said that become attacks on character. Sometimes I think it is safer to just watch the footy and eat pizza.

Social Justice: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly

So, getting back to that list of contentious issues that I wrote. I hear you ask, ‘What’s on that list?’

Like I’m going to say…! By this time, I would guess every reader would have mentally come up with at least three or four.

All right, for the sake of the exercise, I am going to try just one:

Global warming and climate change.

Be honest, did you immediately feel as if you would gravitate to one of these corners? Did you feel your hackles rise? Are you ready to rant?

At ease. I’m not going to talk about global warming and climate change. I don’t know enough about the subject to give any authoritative information. I only used it as an example to show that there are movements in western society with polarised views, and that buying into one side or the other is usually done with passion.

Self-righteousness is not a Christian problem.

Interestingly, over the years I have heard accusations against Christians that they are self-righteous, and I won’t contend with that accusation. The point I would like to highlight here is that self-righteousness is not a Christian problem. It is a human problem. Have you ever been made to feel guilty that you don’t really care about the rain-forests, or some endangered species? While I know that I have been guilty of looking down my nose at someone who is not as spiritual as I am, I also know that most anyone who is passionate about a cause ends up looking down their nose at those who lack that same passion and commitment. Self-righteousness seems to be a by-product of passion and commitment to a good cause. What a circus? Of course we need passion and commitment to good causes (and Christ is as good a cause as any other), but when, by default, we find ourselves sitting on our moral high-horse, looking down on those who have failed to meet the challenge, we have defeated the purpose of all that is good and right. This is what it is to be human. A vicious cycle of doing what is right, and finding out that righteousness doesn’t come that way. Righteousness only comes as a gift of Grace from God.

The thing about most social justice issues is that they provoke self-righteousness, and that does not matter which side of the argument you come from. It is a human problem, and we all wrestle with it because we all think we are right, and cannot understand why others do not agree with our superior position. It is when we are in the right—at least from our point of view—that we are in danger of becoming hot under the collar, which could lead to aggressive and nasty behaviour.

Come, let us reason together

One of the things that bothers me are the options I have when it comes to addressing serious social issues. I am traditionally conservative, but I have been hearing what some of the social justice activists have been saying (particularly if they use a reasonable tone). To stand in the uncertain corner, wringing my hands, seems like a cop out when the issues are often real and they need attention, action and resolution. So what can be done when many ideas and proposed actions are met with aggressive resistance?

When listening to Bible teacher, Shane Willard, I was impressed by the teaching he gave concerning Biblical Hebrew culture. The Scriptures were studied thoroughly, meditated upon, examined. Interpretations were debated and God’s thoughts on the matter were sought. The Hebrew elders would meet at the gate to discuss, but a hallmark of how they went about their discussion was that a debate should always involve loads of questions, and that it should challenge. They examined the Scriptures, but they didn’t believe there was only one right interpretation. They believed the Scripture was like a jewel or a crystal, and it depended on the angle light hit it as to what colour it shone. They believed God spoke through Scripture, but that there were thousands of ways He might speak through one Scripture. It was considered good form to ask intelligent questions. Author, Lois Tverberg, says in her book: ‘…debate was a central aspect of study—the rabbis believed that a mark of an excellent student was his ability to argue well.’[1] Further, she adds: ‘…we are not called to…unquestioningly repeat whatever we learn from a favorite teacher…we are to exercise wisdom and discernment, continually asking questions, weighing answers, seeking understanding and grounding our beliefs within the context of God’s Word…’ This culture is the culture that Jesus was immersed in, and in which he operated. This was a culture that represented a meeting of the minds to determine what God’s mind was on a matter.

Somewhere in the dark ages, following the conversion of the Emperor Constantine to Christianity, the idea of asking questions and debating an issue got lost. Rome had established an ordered empire, and ran it efficiently, but there were no negotiations entered into. It was the will of the Emperor or it was death. The known world of the time was established by brute force, and the Christianity that emerged from the 4th Century on was highly ordered, controlling and used fear of death to keep everyone in line. This did not foster a culture of debating an issue, and finding God’s mind. This fostered fear of being found a heretic and being tortured and/or burned at the stake. Dogma that emerged was inflexible, and Scripture was deemed to have one meaning, and that meaning was dispensed at the will of the clergy. Truth as decided by the clerical authorities was clearly written and proclaimed into the emerging Christian culture, and it was set in stone. This state of affairs continued for a thousand years before the period of enlightenment – the Renaissance and the Reformation.[2]

Galileo, the early astronomer, put forward the theory that the earth moved around the sun, and was threatened with torture, because that was not the position of the holy church. They believed that it contradicted a certain Scripture and he would need to recant. He caved, and took back his “heretical” belief in the face of the cruel pain that would otherwise be inflicted. But in hindsight, he was right. It was just that at that time there was no culture of examining an idea or an issue. That had been lost a thousand years before.

Hebrew culture was about asking questions. They seemed to be inspired by questions, not afraid of them.

Our western Christian culture, though having emerged from the time of witch-hunts and burning heretics at the stake, still at times seems to be afraid of questions. A curious mind is still somehow regarded with suspicion, and yet history has told us that if the many researchers and scientists (who were often men and women of faith) hadn’t been curious and asked questions, then new understanding would not have been gained, and we would still live in the dark ages. There seems to be a residual fear that if we don’t hold to a traditional position, we are somehow a heretic. Almost as if all that is to be known is now known, and there is nothing more to be gained by further investigation. With it comes this idea that I need to have a position, and I need to be right—I have to know the truth or that won’t look good for the Gospel.

Remember, the gospel of Christ is not a political campaign, where we canvas for votes, so that people will vote for Jesus, based on what our policies are. We have seen enough political grandstanding to last a long time. Candidates who stand up and take a position, and have their crowd cheer loudly, while busily slandering the candidate who takes the opposite position.

Is this how Christ asked us to win the lost?

We are afraid of questions, but why? Why are we afraid of not knowing it all—of not having all the answers? After all, it is not possible for anyone to know it all. Not the most studied scientist or philosopher, not the man they say is the smartest man who ever lived, not the most educated theological professor. Not you, not me. No one can possibly know it all. If you are not convinced, I challenge you to a small exercise. It will only take a few minutes. Pop this book down and go to a computer, and put in your search engine, night sky over Uluru, time lapse. A number of short videos will pop up. Take a couple of minutes to watch and note the immensity of the night sky as it moves above us. Take into consideration that what has been filmed is all we can see with the naked eye—we have no concept of how far it extends beyond what we can see. How can any one of us possibly know all there is to know. We are finite—limited. How can we understand the infinite? I have earned a double degree, and yet I am aware that I hardly know anything. That piece of paper from the university means very little when you consider the heavens, when you consider time and what might be outside of time, when you consider life and existence, when you consider God.

Once you come to a place where you can accept that you don’t know everything, and that you will never know everything, and that is OK, then you can relax. We can all relax and not be so quick to defend an idea, a position, or tradition.

Let’s take a look at Scripture:

Isaiah 55:8-10 (NIV) ‘“For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways,” declares the LORD. “As the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts.”’

When it comes down to it, in life we all have opinions and positions, and sometimes we do hotly defend those positions. It is called being dogmatic. But did God ever ask us to make sure we knew everything, and to make sure that we were always right?

Or did He just ask us to seek Him?

Psalm 105:3-4 ‘…let the hearts of those who seek the LORD rejoice. Look to the LORD and his strength; seek his face always.’

Remember, when it comes to seeking truth, truth is not a what. Truth is a who. Jesus said: ‘I am the Way, and the Truth and the Life…’ John 14:6 (NIV)

On my best day of putting together a sermon or an inspirational chapter in a book, I know there is truth in it, but as to me being the fount of all knowledge and wisdom … well that would be barking up the wrong tree.

I am forever grateful that while I speak and write and hope to encourage, that God is gracious. He doesn’t sit up in heaven and fume about all the things I don’t have right, or the things I’ve said that I have not understood correctly. He is pleased when we seek Him and love Him. Just as when a small child draws a stick picture of mummy and daddy, and writes in messy writing, ‘I love you’, the parent doesn’t punish the child because the drawing doesn’t look as it should if a master painter were to have done the portrait. The parent just loves being loved, even if the picture looks ridiculous. This is what God’s love, grace and mercy is about.

If in my life I did everything according to the rules (as I understand them), never put a foot wrong, obeyed every moral code and was in a place you could not fault me, I would be no closer to salvation or pleasing God. That is not how salvation works, and it is not how we please God. My best still only comes up as filthy rags.

Isaiah 64:6 (NIV) ‘...How then can we be saved? All of us have become like one who is unclean, and all our righteous acts are like filthy rags…’

This concept, I daresay, may be offensive to some people who pride themselves in the fact that they are a good person. All I know is, the more I pride myself in how good I am, the worse I am in terms of being judgemental, taking a superior stance and believing myself to be better than others. It is only when I realise that I am just like everyone else in the world—a sinner who is as much in need of the Grace and Mercy of God as everyone else—that I can finally give up my superiority and rest in who God has made me to be.

Romans 3:22-24 (NLT) ‘22 We are made right with God by placing our faith in Jesus Christ. And this is true for everyone who believes, no matter who we are.

23 For everyone has sinned; we all fall short of God’s glorious standard. 24 Yet God, in his grace, freely makes us right in his sight. He did this through Christ Jesus when he freed us from the penalty for our sins.’

What saves me and makes me pleasing to God is His Son, Jesus. When God looks at me, He doesn’t see my inadequacies, sin and self-righteousness. What He sees is the shed blood of his Son, Jesus, having cleansed and redeemed me. This is the only way I can come before Him in right-standing, or righteousness, and it certainly isn’t because of anything I’ve done, no matter how good I think I am.

[1] Spangler, A., Tverberg, L., (2009) Sitting at the Feet of Rabbi Jesus: How the Jewishness of Jesus Can Transform Your Faith, Zondervan, USA

[2] I have spoken of history in broad brush-strokes, coming from my own studies in history. I encourage you to look closer at the history represented here, and do your own research.

Thank you so much Meredith for this insightful commentary on past and present day ways of discussing different and controversial issues! I love your comments on the Biblical culture in the time of Jesus. I too have come to learn that the older I get, the less I know! It is comforting to realise that God is so gracious with us when we can’t work it all out and when we disagree with each other.

Such a good read Meredith.